Jean-Jacques Rousseau was an influential Enlightenment writer whose works are now in the public domain. One of his most famous works is the Discourse on Inequality, in which he talks about how inequality came to be. He eventually concludes that inequality is created by society; men in nature are all equal to one another, and are all better off than men in society. I decided to read this essay and “translate” it into modern-day English.[1] (You may download the translation here and the original here.)

The first thing I noticed about this essay was its scope. In a little more than 40 pages, not only does Rousseau discuss inequality (his main theme), he also makes digressions to talk about the origin of language, what separates humans from animals, and different types of governments. Today, each of these topics can inspire hours of heated debate! Today, anyone who claims to speak the truth about all these topics in a short essay would be deemed a crackpot. Yet, Rousseau got away with it.

I think he got away with it because Europe in 1754 had a very different culture than the western world in 2019. Back then, grand universal truths existed and could be talked about in polite company. Rousseau does not think he is indulging in hubris by telling his readers he has discovered the truth about inequality (and language, what makes humans special, and political theory), and that truth applies across all time and space. He even begins his essay by explicitly addressing all of mankind.[2]

As mankind in general has an interest in this question, I shall try to use a language suitable to all nations. I will ignore the circumstances of this particular time and place in order to think of nothing but the men I speak to. I shall imagine myself in the Lyceum of Athens, with the Platos and the Xenocrates of that famous seat of philosophy as my judges, and with the whole of the human species as my audience.

O reader, whatever country you belong to, whatever your opinions may be, attend to my words.

I can’t imagine any contemporary author, except maybe writers of math and physics textbooks, addressing their work to all mankind across time and space. For example, Steven Pinker’s The Blank Slate, a book about human nature whose topic is certainly applicable to all of mankind, states that it is for intellectuals who “wonder where the taboo against human nature came from and who are willing to explore whether the challenges to the taboo are truly dangerous or just unfamiliar.” Both Pinker and Rousseau are writing for intellectuals: Pinker because that is the most likely audience for a book like his and Rousseau because he wrote the essay as an entry for a contest sponsored by the Academy of Science of Dijon. Both ended up writing for the world at large because their work turned out to be meaningful and important to many people. Yet, only Rousseau explicitly dedicates his book to everyone, perhaps because he was more optimistic than we are about grand universal truths.

Breadth of topics discussed is not the only feature of Rousseau’s writing that gives it a broad scope; he also writes as if he is the first person to write about these topics. Rousseau rarely cites to other authors, which for a modern reader reads as if he is discovering all of this knowledge by himself, for the first time ever. In contrast, modern academic writing is filled with citations running amok. To pick the first example I found, which is by no means egregious, this article about law school clinics includes citations to 12 different sources for its first three sentences.[3] Rousseau cites a similar number of sources for the whole essay. Furthermore, Rousseau’s citations do not just pay homage to the fact that he is standing on the shoulders of giants, as most modern citations do; Rousseau usually cites to disagree. According to Rousseau, Puffendorf makes a “a very poor argument” about liberty, Hobbes’ conclusions about the inherent nature of man are “flawed,” and even Plato was mistaken to think that “perfect happiness … consists in … obeying [the] prince.”

Rousseau wrote in a world where reason could uncover universal truths. He did not yet know about the pitfalls of the scientific method or the confusingness of quantum physics. With the benefit of having used reason for more than 200 years, we now know that the path from reason to universal truths is long and treacherous. Rousseau, having no such knowledge, could make all sorts of assertions preceded by only the barest disclaimer:

I must own that the events I am about to describe might have happened many different ways and I have guessed what really occurred. These conjectures are the most probable of all events that could have occurred, and they are the only means we have of discovering truth. Besides, the consequences I discuss will not be merely conjectural, since it is impossible to form any other system that would not give me the same conclusions.[4]

His fearlessness is admirable! He admits his theories may be wrong, but he says his conclusions stand independent of those theories. There is no cover-your-ass language here. No “most evidence indicates...” or “my best guess is that...” He is convinced that reason has not led him astray in any significant way, even if nitpickers manage to find faults with some of the details.

I’ll leave it to individual readers to judge for themselves whether Rousseau’s conclusions are correct. His theories, unfortunately, are often incorrect, which is not surprising because he bases them on pure conjecture. They often reminded me of dad theories.

One example of a dad theory

One example of a dad theory

Another example of a dad theory

Another example of a dad theory

My favorite dad theory in the entire essay is the theory that language must have originated on islands, because on islands, humans were forced to live and work in tight quarters for lack of space, so they were forced to come up with languages to interact with each other. People on continents used the space available to them to live in solitude, and because they avoided interactions with each other, they never needed language. Runner-ups include the claim that as people age, their “demand for food decreases in proportion to the ability to find food.” That would be poetic if it were true, and would make the future of Social Security a lot less precarious. Rousseau also claims that animals do not have free will because pigeons cannot choose to eat meat and cats cannot choose to eat fruit. However, I am not convinced that dietary restrictions have metaphysical implications, and that humans’ omnivore diets are a symptom of our free will.

A lot of the text waxes nostalgic for how perfect life was for humans back when they lived in a state of nature, and how much worse life is in the present day. What is most interesting about these sections of the essay is how similar Rousseau’s thoughts are to those I often hear around me. Nostalgia for a better past seems to take the same shape, even today.

Some other parts of the essay also felt surprisingly relevant to the present day. Rousseau tears down rich people who say “I built this wall. I own this spot due to my labour.” This echoes Obama’s famous “you didn’t build that” line. Rousseau talks about “some great souls, who consider themselves as citizens of the world and follow the example of God to make the whole human race the object of their benevolence.” In contrast, Theresa May recently gave a speech about Brexit where she was decidedly less complimentary towards citizens of the world.

Click here to see a redline of the changes I’ve made.[5] The first thing you’ll see is that there is more red (deletions) than light blue (additions). Throughout the translation process, I felt like I was taking rich layered digressions and turning them into…

This is due to a personal bias. I have trouble understanding stream-of-consciousness writing, especially if it is filled with digressions as well.[6] My translation made the sentences shorter and more direct. The charts below provide a closer look, with statistics about the original text in black and those about my translation in red.

Sentences with more than 80 words are virtually non-existent in my translation, and most sentences have less than 50 words. Short sentences mean the text has less time to meander. How did I make the sentences shorter? I had two main strategies:

First, I cut out text that seemed tangential. Often, this meant cutting out a lot of text. For example, here is a sentence from Rousseau:

Hence the first duties of civility and politeness, even among savages; and hence every voluntary injury became an affront, as besides the mischief, which resulted from it as an injury, the party offended was sure to find in it a contempt for his person more intolerable than the mischief itself.

This is a single sentence of 50 words, the gist of which is to say that men in nature eventually began to be more civil and polite. My translation gets to the point more quickly:

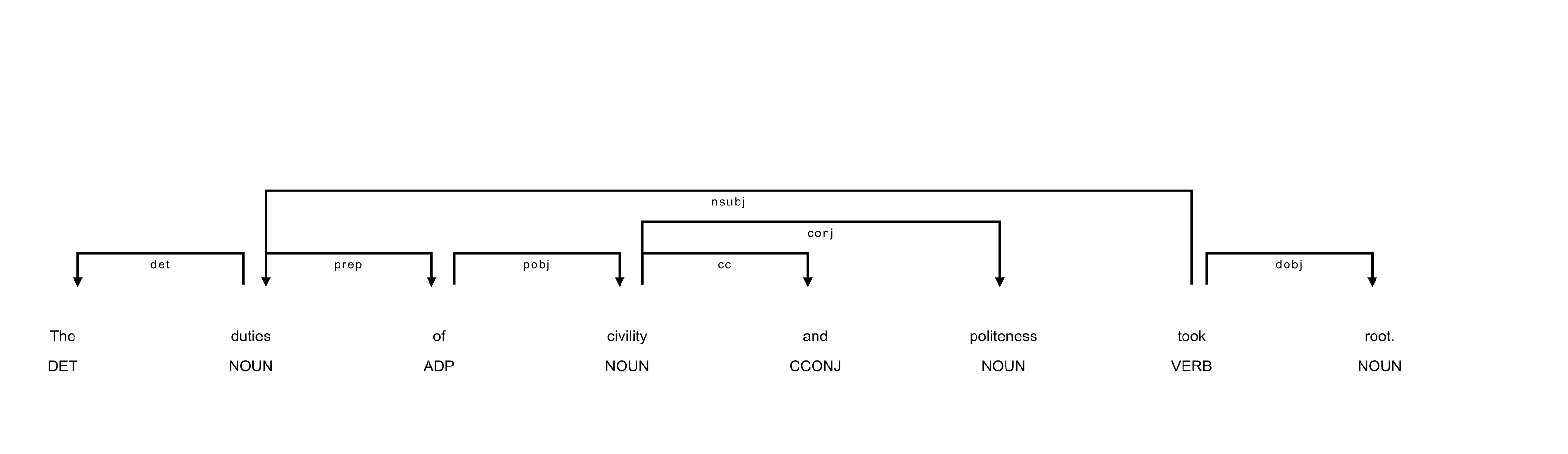

The duties of civility and politeness took root.

It’s true that the translation is not as poetic as the original, and does not explain the phenomenon quite as thoroughly. However, I am much more likely to finish a book if it is written in the latter style. Also, to me, the phenomenon did not need as much explanation as the original gave it. This is a matter of judgment, and in my judgment, people are likely to accept that civility and politeness came into existence without needing an explanation of how injuries began to cause offence and contempt, especially when the explanation is not central to the theme of the essay.

Second, I split up single sentences into many smaller sentences. For example, here is a sentence from Rousseau:

Let us consider how many ideas we owe to the use of speech; how much grammar exercises, and facilitates the operations of the mind; let us, besides, reflect on the immense pains and time that the first invention of languages must have required: Let us add these reflections to the preceding; and then we may judge how many thousand ages must have been requisite to develop successively the operations, which the human mind is capable of producing.

This sentence forms a paragraph in the original text, and includes so many ideas![7] Here, in my judgment, the ideas are all important, and so should not be cut out. However, the reader does need some pause between them. My translation keeps all the ideas, but splits them into four sentences. I also tried to keep the parallelism Rousseau had in the original (let us… let us… let us…) by starting the first three sentences with verbs (consider… consider… reflect…).

Consider how many ideas we owe to the use of speech. Consider how much grammar exercises the mind. Reflect on the immense labor and time the invention of languages must have required. Now we may judge how many thousand ages must have been needed to develop the functions the human mind is now capable of performing.

Not only did I make the sentences shorter, I also tried to make them less complex. You can see the transformation in the tree diagrams of sentences, before and after. Tree diagrams determine what part-of-speech each word is, and how it is dependent on other words.[8] Each tree diagram has two properties: the tree width and the tree height. The tree width is the number of leaf nodes in the tree (i.e., words with arrows coming into them, but no arrows going out of them). The tree height is the maximum number of words between the root node (i.e., a word with no arrows coming into it) and a leaf node (i.e., a word with no arrows coming out of it). For example, compare the two tree diagrams below.

Below is a chart showing the tree width and height for all the sentences in the original text and in my translation. The size of each dot shows how many sentences in the work had that tree width and height. Because so many dots lie on top of each other, especially for the translation, the lines graphs on the x- and y-axis make clearer the relative distribution of tree widths and heights for both texts.[9]

As you can see, my translation has trees of smaller widths and heights, while the original text had much greater variation in those values. This means that the sentences in my translation are simpler than those in the original work.

▲ [1] I’m not the only one with this idea. Early Modern Texts a is a website that translates many philosophical works to modern English, and also adds notations to make understanding them easier. Rousseau’s other famous work, The Social Contract, is available there.

▲ [2] This quote, and all following quotes, cite to my translated essay unless otherwise noted.

▲ [3] The first three sentences are: “Debates about how to educate law students have long rotated around a familiar axis — the theory/practice divide. Commentators and bar associations routinely rebuke legal education for being too theoretically oriented. A recent iteration of that debate has centered on the credit hours that must be devoted to experiential learning.” None of these sentences seems so controversial that it would be unbelievable without citations.

▲ [4] This is only one of the many disclaimers he uses throughout his work, but it is exemplary of the rest. Another disclaimer, which seems hilarious by contemporary standards, reads “Let us begin by putting aside facts, for they do not affect the question.”

▲ [5] Note that I am translating a 1910 translation of a French work written in 1754. The discussion below treats the 1910 English translation as being faithful to the 1754 French text. If it wasn’t, then the discussion below is erroneously attributing writing characteristics to Rousseau when they could have been an artifact of the translation.

▲ [6] I’ve never, despite multiple attempts, been able to finish James Joyce’s Ulysses.

▲ [7] The original text uses a lot of semicolons in similar situations: to join many ideas into a single, extremely long, sentence. The original text has 387 semicolons, which I reduced to 62 in the translation, mainly by splitting up long sentences into smaller ones.

▲ [8] You can play around with creating tree diagrams for sentences here.

▲ [9] Chart inspired by Tufte. Charts more faithful to his original style can be seen here.