Many people from my generation spent ages 8-13 fantasizing about receiving a letter from Hogwarts. The fact that we were average in every measurable way only cemented the fantasy; after all, in the stories, if you encounter an average protagonist, you can bet that a life-changing power or prophecy is coming down the line before the first act is over. So, dear reader, imagine my joy when, many years after having resigned myself to being ordinary in every way, I finally found out that I’m special! What’s my rare talent, you ask? I am ~*~*~under-confident~*~*~.

Let me back up. I did a calibration assessment on myself to measure my confidence. To perform the calibration assessment, I found a series of trivia questions, for example: What is the tallest building in the world? I first answered the question (Burj Khalifa) and then wrote down how confident I was in my answer (60%). Once I had answered a couple hundred questions, I analyzed my answers. To be perfectly calibrated (that is, to be neither underconfident nor overconfident), I should have been correct 60% of the time for questions where I was 60% confident, 70% of the time for questions where I was 70% confident, 80% of the time for questions where I was 80% confident, and so on.

Most people who do calibration assessments tend to be overconfident. And not just slightly overconfident, but ridiculously overconfident. People who say they are 80% confident tend to be correct only 60% of the time, and people who say they are 100% confident tend to be correct only 80% of the time. Imagine a coworker who gets every decision wrong on Wednesdays, but still insists he has never made a mistake. To get a sense of how prevalent overconfidence is, you can read this summary of calibration experiments that says “overconfidence is found in most tasks,” and mentions overconfiden* 50 times and underconfiden* only 11 times. Granted, the document is from the 1980s, but I don’t think human nature has changed much since then, at least for the majority of the population not on Twitter.

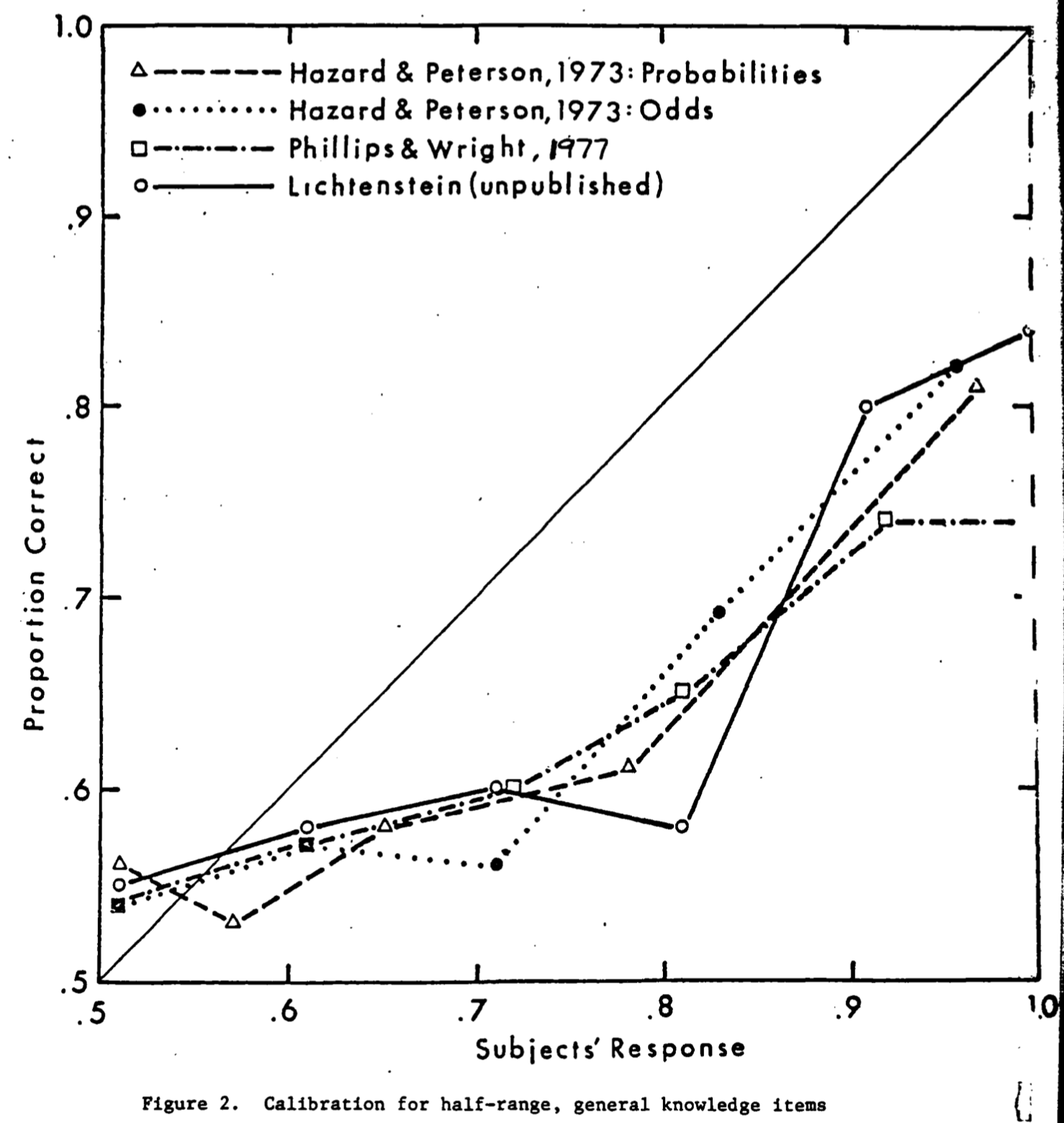

Some examples of typical calibration curves. Notice that they are below the perfect calibration line, indicating overconfidence. Source.

Some examples of typical calibration curves. Notice that they are below the perfect calibration line, indicating overconfidence. Source.

Before I started this calibration, I knew that most people tend to be overconfident. I fully expected myself to be overconfident as well. I was shocked to find out that I tend to be underconfident, and by quite a large margin. When I think I am flipping coins, I am actually waiting for death and taxes. I feel vindicated and regretful thinking back to all the group projects where I had some version of the following conversation:

Me: I’m 60% [actually 90%] sure the right answer is X.

Overconfident normal person: I’m 99% [actually 80%] sure the right answer is Y.

Me: Okay, let’s do it your way.

I have some hypotheses for why I did not realize I was underconfident before this exercise: